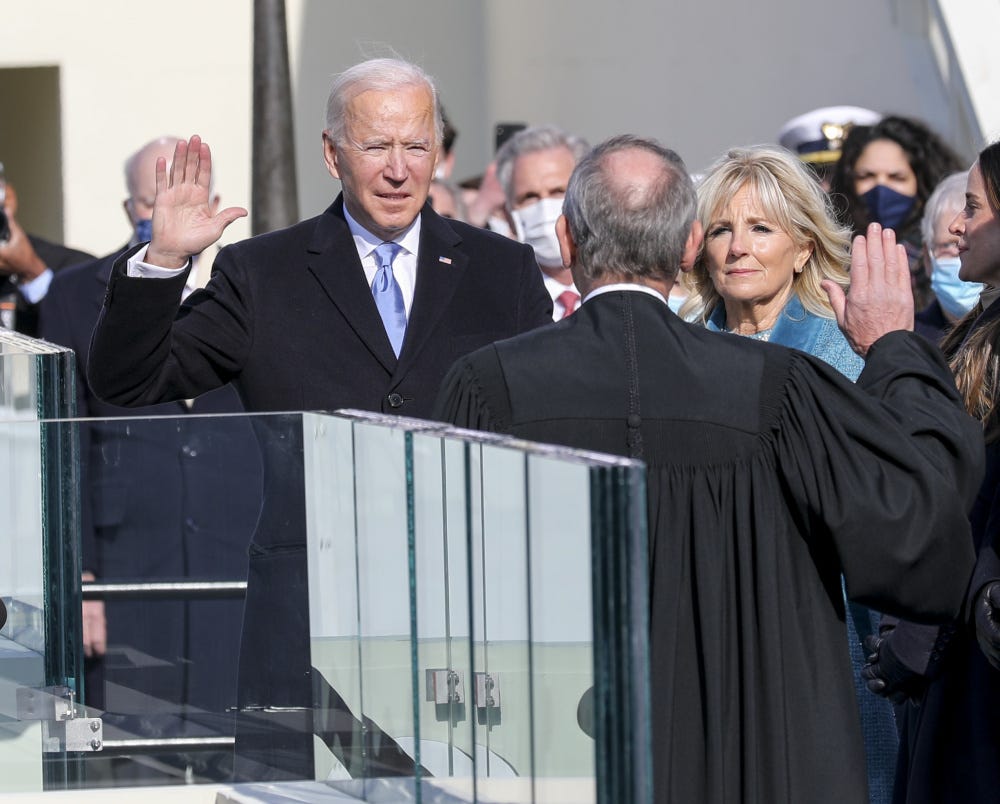

Forty Six

Joe Biden is inaugurated. And the work begins.

Welcome back to another issue of Blunt Reentry.

I’m writing this on the eve of the 21st of January. Joe Biden was inaugurated as the forty-sixth president of the United States. There’s a new administration in Washington and there’s just so much to be done—not just to undo the damage of the last four years, but to build a better, more just world.

2020 wa…