China, U.S. Intelligence, and Nuclear Weapons Testing

Parsing out a new, specific U.S. claim.

I was going to write something on the expiration of New START, but Chinese nuclear-testing is just much more interesting to me. So here’s today’s NukesLetter.

Thomas DiNanno, the U.S. under-secretary of state for Arms Control and International Security, publicly offered a new, previously classified U.S. assessment of Chinese nuclear testing activity. Here’s what he said at the Conference on Disarmament in Geneva. I’ve bolded the bits that most pique my interest.

Today, I can reveal that the U.S. Government is aware that China has conducted nuclear explosive tests, including preparing for tests with designated yields in the hundreds of tons. The PLA sought to conceal testing by obfuscating the nuclear explosions because it recognized these tests violate test ban commitments. China has used decoupling – a method to decrease the effectiveness of seismic monitoring – to hide their activities from the world. China conducted one such yield producing nuclear test on June 22 of 2020.

The detail on decoupling—i.e., detonating nuclear explosives within an underground cavity to obfuscate seismic signatures—offers official confirmation of a detail that I think was first reported by the Wall Street Journal back in April 2020 (notably, a few months before June 22, 2020).

Previous U.S. arms control compliance reports have been more ambiguous on China’s alleged activities of concern at Lop Nur than on Russian activities. The 2021 compliance report (the first after the alleged June 2020 test) noted:

China’s possible preparation to operate its Lop Nur test site year-round and lack of transparency on its nuclear testing activities – have raised concerns regarding its adherence to the U.S. “zero yield” nuclear weapons testing moratorium adhered to by the United States, United Kingdom, and France.

As a reminder, the “zero yield” standard is the U.S. interpretation of what the Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty (which neither the U.S. or China have ratified) means with its ban on nuclear tests: no tests that produce “a self-sustaining, supercritical chain reaction of any kind.” Self-sustaining supercritical chain reactions are present in what most people (including the current president of the United States) imagine when they picture a nuclear weapons explosion. They are also present is so-called “hydronuclear” experiments, where a small explosive yield (measured potentially in kilograms) is released. These types of experiments are incompatible with the zero-yield standard that the U.S. uses to assess compliance with nuclear test-ban commitments.

I’d assumed that U.S. allegations to date likely concerned Chinese hydronuclear experiments, but I’m now revisiting that. DiNanno’s claim is ambiguous on this point, but it does not appear that the yield under question is likely to be in the multi-single-digit-kilogram range if decoupling is being used at Lop Nur.

Rather, what’s most interesting to me is that the United States appears to have intelligence about the designated yields of Chinese nuclear weapons experiments. In fact, DiNanno’s willingness to share this tells us something about why the U.S. has been rather cagey about Chinese testing activity since the alleged test in June 2020, despite the strong incentives to build all kinds of a case around Beijing’s nuclear build-up and changing posture. Fundamentally, this suggests the U.S. has probably relied on exceptionally sensitive sources and methods (possibly SIGINT, but perhaps HUMINT—hello, Gen. Zhang Youxia? Editor’s Note: Just Kidding.) to support National Technical Means-derived assessments about whatever is happening at Lop Nur. Essentially, it does not seem implausible that DiNanno’s point about designated yields is based on certain higher-confidence intelligence inputs about the technical parameters to which China is testing.

The specific observation about the PLA recognizing a violation of CTBT commitments is less clear to me, to be clear; this could be based on similarly sensitive intelligence inputs: for instance, SIGINT picking up chatter from PLA personnel involved in test instrumentation and design discussing “We better do x and y so this test with z designated yield doesn’t violate the CTBT,” or it’s just color for this speech. The language seems less specific here (at least, in the sense of how U.S. intelligence assessments are normally parsed out in speeches and public reports like this).

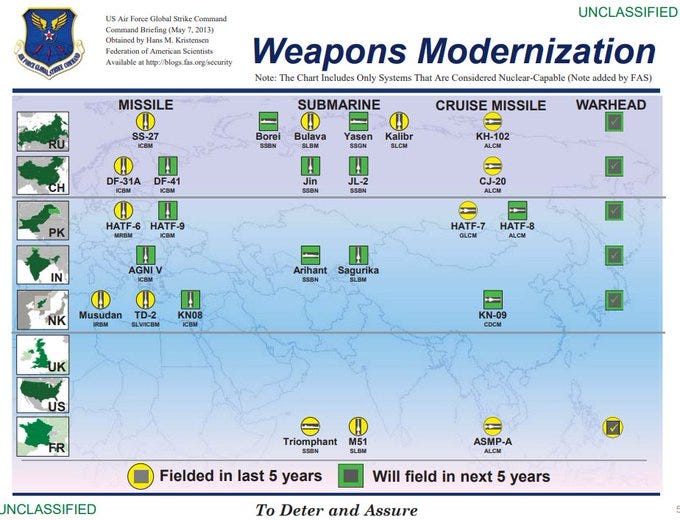

What also seems important to point out here is that, I think, DiNanno is being clear that the U.S. is sitting on intelligence that China has designs for future testing and experimentation that could result in testing resulting in yields in excess of 100t: that’s well beyond the hydronuclear yield expectation and—probably—useful for the development of confidence1 around new physics packages for platforms like hypersonic glide vehicles and, possibly, cruise missiles. There are also one-point safety benefits to very-low-yield hydronuclear experiments, which the U.S. carried out during its own 1958-1961 nuclear testing moratorium.2 (China does not have any acknowledged nuclear-capable cruise missiles, nor have there been sustained U.S. intelligence assessments to this end.3)

It would be interesting to find out whether tests to 100t yields would necessitate the excavation of new cavities at Lop Nur beyond what already exists. There may be useful open-source indicators.

The Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Organization’s executive secretary, Rob Floyd, has released a statement in “response to media enquiries” about DiNanno’s remarks, by the way. What confuses me here is that it appears Floyd (or rather his staff) parse DiNanno’s comments rather differently and note that regarding “reports of possible nuclear tests with yields in the hundreds of tonnes, on 22 June 2020, the CTBTO’s IMS did not detect any event consistent with the characteristics of a nuclear weapon test explosion at that time.”

That’s … fine, but I’m not sure DiNanno alleges that there actually have been tests “with yields in the hundreds of tonnes” (rather, these are planned tests with a designated yield in that range). Usefully, Floyd does point out the limitations of the IMS’ capabilities, which fall off on confidence in detecting man-made nuclear seismic events below 500t. (As an aside, it is interesting to ponder China’s own confidence levels on obscuring 100t+ yield events from the CTBTO IMS and other seismic sensors—even with geologically exceptional full-scale decoupling. I haven’t done the math, but detection risks seem … high? It’s not obvious that this is the case in the sub-100t-but-above-a-few-kg yield range, especially at lower ends.)

So, what’s the policy upshot on all this? Well, the U.S. position, per POTUS, has been that it will seek to test “on an equal equal basis” (which DiNanno restated) as other countries. So, presumably, that would mean that hydronuclear experiments with self-sustaining supercritical chain reactions and larger multi-deca-ton yield-generating experiments are now on the U.S. menu. Among the many problems with the U.S. position is that Washington still has a Sino-Russian deniability problem to get around. What the U.S. is proposing is to explicitly and deliberately violate its own zero-yield standard, which would also mean that it would potentially seek to openly violate the CTBT. While Russia and China are carrying out experiments with opacity, they would not be in the position of openly being the first nuclear-possessing state outside of North Korea in the twenty-first century to openly carry out yield-generating tests. The net benefit for the U.S. technical, diplomatic, and strategic position is … rather dubious, as a result. (I won’t reiterate the technical case here for why testing is unnecessary for the U.S., but here’s former LANL Director Sig Hecker on that topic in Foreign Affairs.)

Either way, I think the finger-pointing on nuclear-testing is far from done at this point. China’s reaction to DiNanno’s CD comments has been predictably light on engaging with the substance of U.S. allegations, but I’d expect this to continue—including probably at the upcoming Nonproliferation Treaty Review Conference.

For a moment of zen this fair New START-expiration-week Friday, here’s a fun declassified 1964 memorandum for the Johnson White House on all the reasons not to attack China’s nuclear test site at Lop Nur. It’s quite the read and an all-timer in the annals of counterproliferation primary sources, in my humble opinion. (Hello, Midnight Hammer!)

See Table 4-3 in this 2012 National Academies of Science study on the relative value of different magnitudes of nuclear tests. The sub-1t range, in their conclusion, is mostly useful for building confidence and experiments, but also supporting some safety issues. The military significance of these activities is probably going to have big error bars in our unclassified debates.

On the U.S. 1958-1961 hydronuclear experiments. “Hydronuclear experiments, a method for assessing some aspects of nuclear weapon safety, were conducted at Los Alamos during the 1958 to 1961 moratorium on nuclear testing. The experiments resulted in subcritical multiplying assemblies or a very slight degree of supercriticality and, in some cases, involved a slight, but insignificant, fission energy release. These experiments helped to identify so-called one-point safety problems associated with some of the nuclear weapons systems of that time. The need for remedial action was demonstrated, although some of the necessary design changes could not be made until after the resumption of weapons testing at the end of 1961.”